Southwestern Jefferson County’s Place in National History

Cat Carson September 2019

This is the story of Donald E. Distler, who in 1977 set the bar for federal criminal charges against a defendant in a pollution case. He was sentenced to 2 years in federal prison, and a $50,000 fine. It was the harshest sentence ever for a pollution charge, a Landmark Decision.

Mr Distler grew up on Distler Road, in southwestern Jefferson County in the 1950’s & 60’s. There wasn’t a lot of pollution control in those days.

Chemically speaking, our world is a very scary place. The industrial age has created some pretty toxic byproducts. Some of them kill you outright, just by breathing or touching them. Others just give you cancer, foul the environment, kill critters, and usually stink something awful. And almost all of these toxic chemicals last for years and years.

Beginning as early as spring of 1957, Mr. Distler was burning something that “gave off a stench” on the Distler property. The clipping below is from the Courier Journal.

I have spoken with several area residents that grew up around this property. I was told the “lake” mentioned below was actually a large sinkhole. And if you’re looking for a bottomless hole to throw stuff in, that’s what a sinkhole is.

Those same folks also all said that no one in the neighborhood was the least bit surprised that things turned out like they did. They all told the same stories of barrels in the “oddly colored pond”, barrels sitting and scattered about, a horrible smell, and the sound of a tractor working in the woods, yet nothing was ever built. So I believe the story really starts there.

I also believe Mr. Distler got his start in the chemical waste disposal business at a very young age. Perhaps he worked for Mr. Arthur Taylor as a young man. Mr. Taylor had been stashing barrels since the 50’s. Mr Taylor owned the property that would go on to become The Valley of the Drums. It was a history making amount of toxic waste on a rural Bullitt County farm. It was the nation’s first Superfund site.

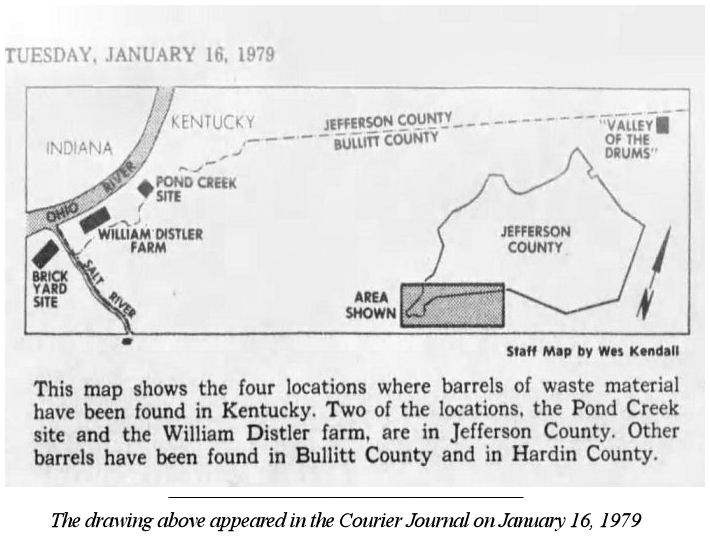

Again, that’s simply my speculation, no connection can be proven. However, Mr. Distler was found to be responsible for several sites in the same area, around the same time. (Two of them went on to also become national Superfund sites.) So I will assume they had probably chatted, just saying.

By the early 1970’s Donald Distler was hauling toxic waste from companies in several states. He advertised his company, Kentucky Liquid Recycling by saying, “Help Us Clean The World”.

In 1975, the Lee’s Lane Landfill (at the time, the county’s largest) was found to contain an unknown amount of toxic waste. It was believed to have been dumped between 1970 and 1975. Eight families were forced to evacuate. No one was ever held really accountable. MSD was identified as a possible contributor. The Landfill closed permanently in 1975.

By the mid 70’s Mr. Distler had bought a toxic waste incinerator, with the intention of setting it up in Jefferson County. He was denied a permit.

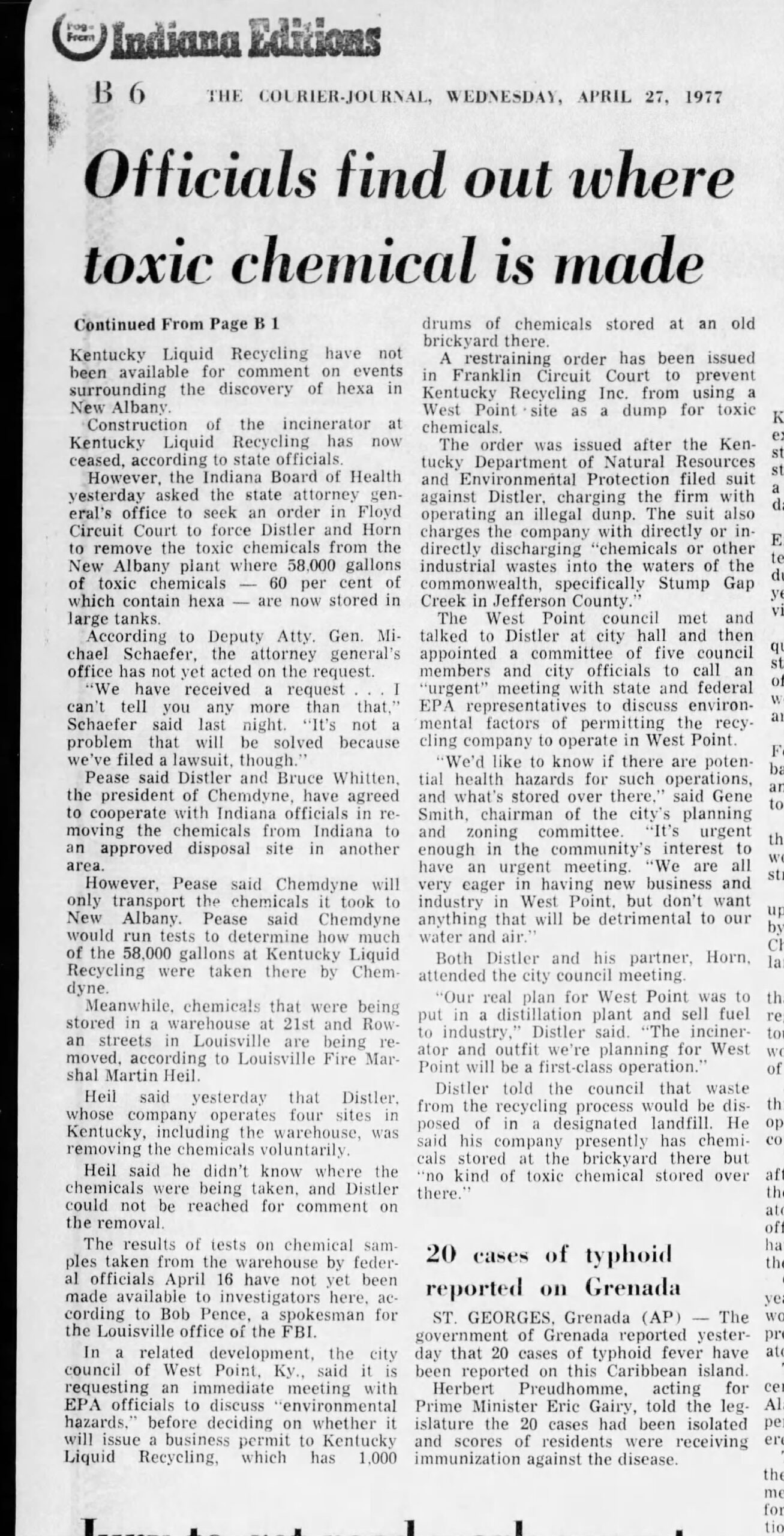

In March 1977 he leased an abandoned brickyard in Hardin County and applied for a permit to install & operate it there. But West Point denied the permit.

He had previously leased an old Standard Oil property with a warehouse, a tank farm of 10 empty tanks, and a large storage basin. Apparently this is where he housed the Hexa & Octa, the most toxic of the chemicals he was holding. So he applied for a permit in Indiana, and built a smokestack for the burner.

During this time, he never stopped hauling truckloads of toxic chemicals. He was telling the companies he had a working incinerator, as he waited for the permit. And the drums continued to stack up. Where was it all going? Did he stash them in some building, empty them on the ground, into the river, into the sewer, or bury them on someone’s farm out in the rural county? He denied it all.

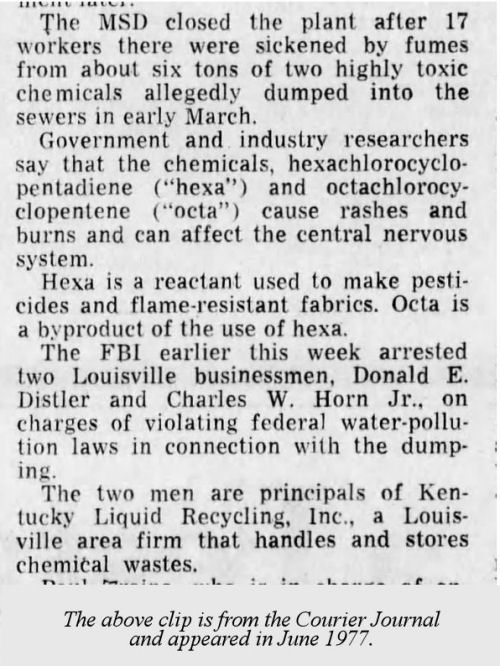

But it all hit the wall when the Morris Forman Sewage Treatment Plant in Louisville had to shutdown for months due to contamination from Hexa and Octa (nasty stuff) in March 1977. The city was forced to dump millions of gallons of raw sewage into the Ohio river while the plant was being cleaned.

Because it was a public waterway, the FBI moved in and opened an investigation. The city offered a $5000 reward for information that would lead to the arrest of the person responsible for the mess. Someone stepped forward with information, and the bad juju came hot and fast.

Mr. Distler was convicted of 2 counts of illegal handling of hazardous waste in The US District Court in December 1978.

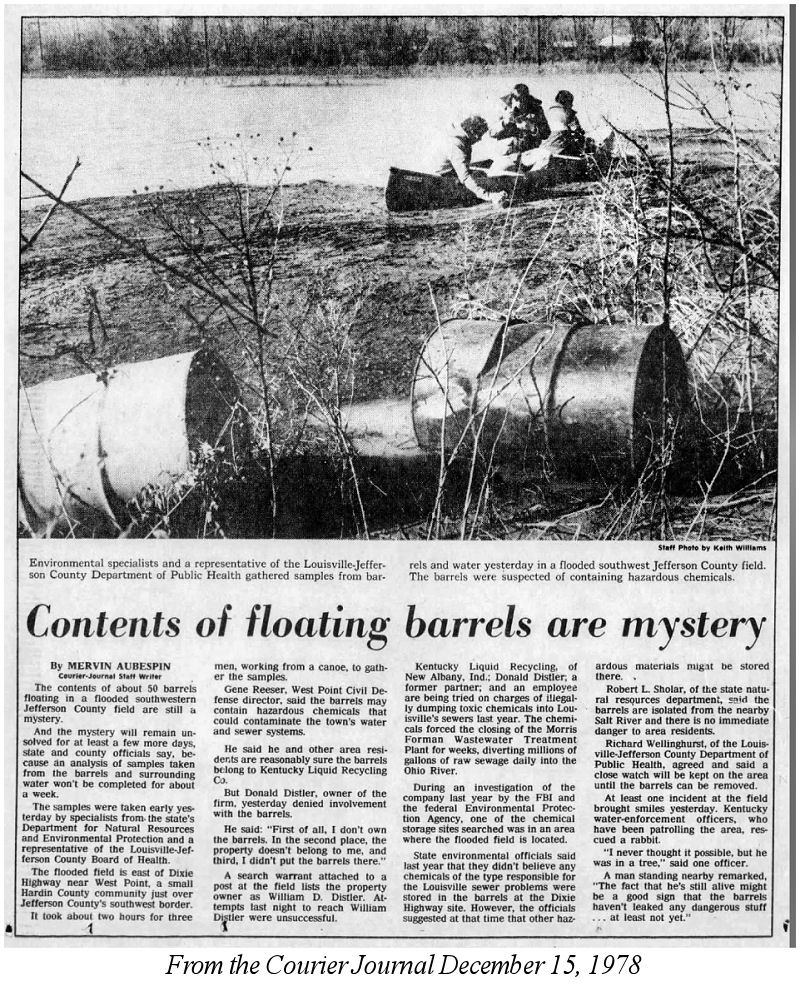

Then things got even worse. While he was in court awaiting sentencing (his partner had been acquitted) Jefferson County had a big rain storm. 1,000 barrels were found floating in a field on a farm south of Louisville, that belonged to Donald Distler’s father William. The farm had been searched earlier, but heavy rain changes everything.

Shortly after that, the city of West Point filed suit to stop the dumping at the Brickyard in Hardin County. Then New Albany filed suit, giving him a deadline to clear the thousands of gallons of toxic hexa and empty the tanks.

As the story grinds slowly to a very contaminated end, Donald Distler was found to be connected to at least six sites storing toxic waste. The Distler Farm and The Brickyard both became Superfund sites.

But there was a warehouse on Rowan Street, a building at 30th & Griffith that was in his wife’s name, and the New Albany warehouse, in addition to the multiple dump sites south of Louisville.

Yet the family property where Mr. Distler grew up, has never been tested. Mr. Distler had access to the sizable sinkholes on that property during the the late 70’s, while he was juggling barrels of toxic waste from one site to the other. Yet not one test was ever done on the place that carries the Distler name. I think that’s darkly ironic.

The C2 zoning was approved, the barrels disappeared, the sinkhole/lake with the film across the top was backfilled, and a new pond was dug. Everything was leveled and the ballfield was built. It still makes me wonder what all those folks playing ball rolled, and slid through.

________________

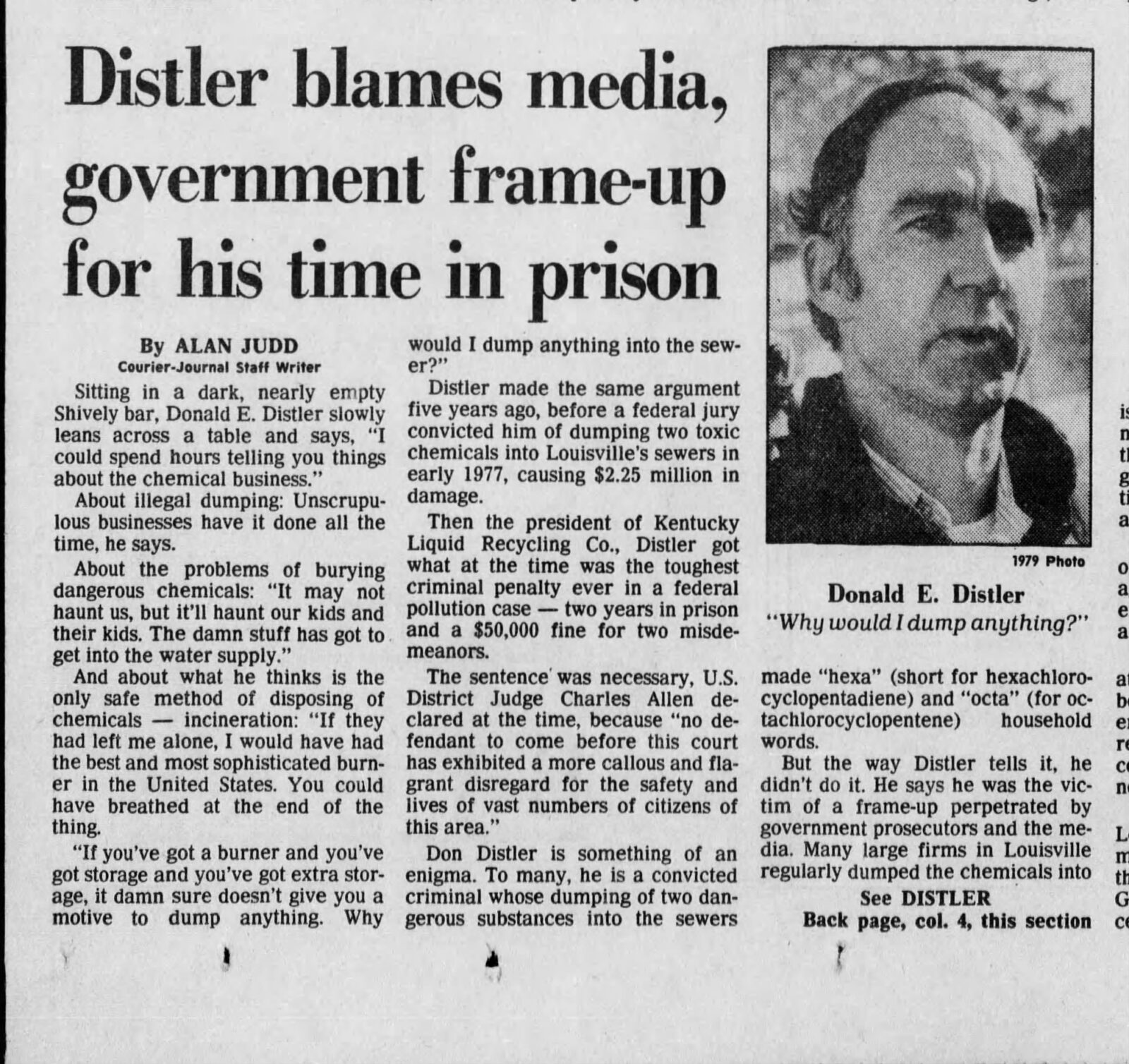

Mr. Distler denied all of the charges from the very beginning. In the interest of fairness, this article ran in the Courier Journal on September 27, 1983, after he was released from jail.

______________________________

And it didn’t stop. Mr. Distler found himself back in court as the feds tried to recover costs:

August 1992